Post Infectious Irritable Bowel Syndrome

Post-Infectious IBS is the name given to a condition suffered by a number of patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome who report that they had normal bowel habits prior to a bout of gastroenteritis, diarrhoea and/or vomiting. Post-Infectious IBS without concurrent anxiety, depression, or other mood symptoms is usually a good prognosis with a fast recovery time. The most common causes of the gastroenteritis are viral, followed by Campylobacter, Salmonella and Shigella. Viral gastroenteritis typically heals rapidly and there is little residual damage to the gastrointestinal wall. However, bacterial gastroenteritis can cause forwards ulceration and bleeding, and is more likely to be associated with Post-Infective IBS.

This description of Post-Infectious IBS is based largely on the work of Dr Robin C. Spiller, MD and colleagues from the University Hospital, Nottingham. However, we recommend treatments based on our own work in conjunction with Bioscreen Medical. Spiller gained data from a community survey, which identified 386 cases of bacterial gastroenteritis. The average duration of illness was seven days with a third of patients reporting bloody diarrhoea and a median weight loss of 6kg. Travellers’ diarrhoea is very common in Australians travelling to Asia and Indonesia, as it is in Canadian citizens travelling to Mexico. In one study of Canadian travellers nearly 50% developed travellers diarrhea. The incidence of new IBS three months later was 17.5%, compared with 2.7% of people who did not develop travellers diarrhoea.

Risk Factors of Post Infectious IBS

Diarrhoea and vomiting are normal reactions to infection and help clear the gastrointestinal tract of infection. Most patients with bacterial gastroenteritis fully recover and only about 10% appear to develop Post-Infective IBS. The risk factors are:

- Being of the female sex;

- Hypochondriasis (although it could be argued that the ‘hypochondriasis’ is the result of a predisposing weakness);

- Adverse life events in the previous year;

- The severity of tissue damage and ulceration may be major predictor.

The duration of the initial illness is a very strong risk factor for Post-Infective IBS. The specific infectious bacteria are also likely to be important, since Spiller found that around 10% of people infected with Campylobacter developed Post-Infective IBS, compared to just 1% with Salmonella.

Post Infectious IBS Pathophysiology

Diarrhea-related illnesses are characterised by faster gastrointestinal transit time and increased gut sensitivity. This gradually returns to normal, but often at a variable rate. By three months, most of those who are going to recover will have done so, and thereafter the rate of recovery is much slower.

Spiller and colleagues performed longitudinal rectal biopsies in individuals recovering from Campylobacter gastroenteritis at 2, 6, 12 and 52 weeks. They noted initial increases in both inflammatory cells and entero-endocrine cells. Most of these markers returned to normal, but in a few markedly symptomatic individuals the biopsies remained abnormal. Similar abnormalities were noted in outpatients with a history of Post-Infectious IBS. There is a strong correlation between the inflammatory cells and the entero-endocrine cells, and Spiller suggests that this is because cytokines drive the entero-endocrine cell hyperplasia. Preliminary research also notes increased entero-endocrine cells in unselected IBS patients. More importantly, is the increase in 5HTP associated with IBS. Pilot studies suggest there is also an exaggerated release of 5HTP post-meal, particularly in IBS sufferers with meal-related symptoms.

Treatment of Post-Infectious IBS

It is important that patients understand the important roles of anxiety, stress, diet and persisting low-grade inflammation related to Post-Infectious IBS. If the Rome criteria is met, and general physical examination is normal, then the probability of an alternative diagnosis is low. However, gut infections can be a sign of other diseases such as celiac disease, inflammatory bowel disease (e.g., Crohn’s) and tropical sprue together with hypolactasia. Therefore, symptomatic patients should undergo a minimum set of screening tests, including endomysial antibodies, haemoglobin, CRP, ESR, albumin and stool culture tests.

In the absence of weight loss, fever, rectal bleeding, and nocturnal diarrhoea, only 5% of all these tests are likely to be abnormal. Since microscopic colitis also develops acutely after an infectious illness, we recommend a colonic biopsy and, if suspicions are high, also a duodenal biopsy to exclude celiac disease.

Lactose intolerance develops after a viral gastroenteritis and is well recognised by paediatricians. It occurs often in infancy when lactase, the enzyme responsible for digesting lactose, is only fully expressed in the mature enterocyte at the tip of the villus.

Since viral gastroenteritis causes specific damage to the villi, lactase levels remain low for some months. A low lactose diet is, therefore, worth trying.

The co-morbid psychological factors associated with IBS, such as anxiety and depression, should also be treated.It is unlikely that a person will fully recover from IBS without addressing their mood disturbances.

At BNC, we recommend a diet that excludes foods for which the patient has a demonstrated IgG sensitivity (from ELIZA assay). In addition, we recommend a controlled reduction of poorly absorbed carbohydrates (FODMAPS), such as fructose wheat and gluten grains, potatoes, and citrus fruits. Any foods that the patient feels particularly sensitive to are also eliminated or reduced.

At BNC, food elimination, specific probiotics (beneficial bacteria), and nutritional supplementation, are all major components of treatment for IBS regardless of the cause. To summarise our approach:

- Eliminating food intolerances reduces the inflammation in the gut wall.

- Specific nutrients can repair the gut wall.

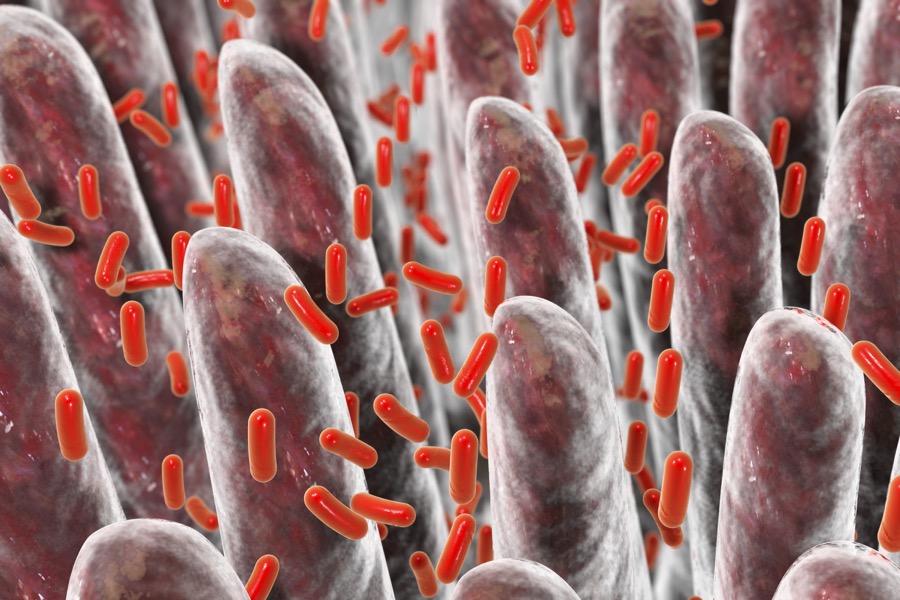

- Reintroducing beneficial bacteria that competes with, and controls, the excessive growth of commensal bacteria that maintains the IBS.