Causes, Symptoms and Treatment of Post-Concussion Syndrome

What is Post-Concussion Syndrome

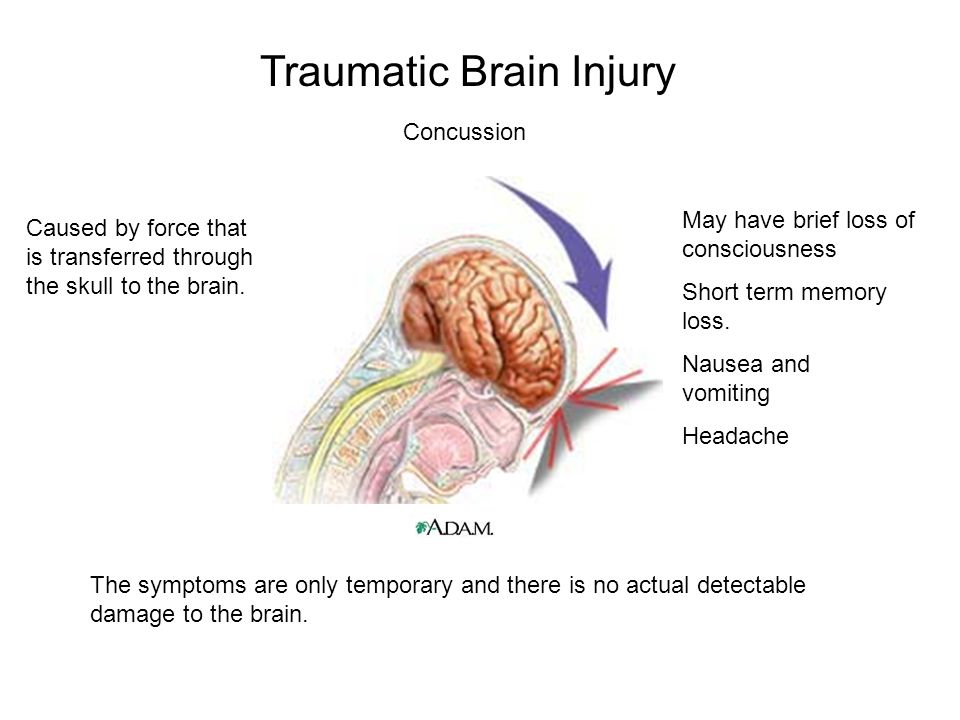

After a forceful blow to the head, the brain can move differently from the skull, leading to traumatic brain injuries (TBI). While much of the initial damage occurs at the point of impact, the brain’s frontal and temporal lobes are particularly susceptible to bruising—contusions—because of the way shock waves and shearing forces affect this delicate tissue. In some cases, a pressure wave travels through the brain and causes a “contrecoup” injury, resulting in additional contusions on the side opposite the initial impact. These forces can also shear axons at the junction of white and gray matter, further damaging neural connections (NIH Bookshelf; NIH Bookshelf on contrecoup injury).

The terms Post-Concussion Syndrome (PCS) or Post-Concussive Disorder refer to a collection of lingering symptoms that can persist long after a mild head injury. Although such injuries are typically considered minor, a significant number of people continue to experience symptoms for weeks, months, or even years after the event. These symptoms often include headaches, memory issues, difficulty socialising, and personality changes, and can overlap with conditions like Attention Deficit Disorder, Adjustment Disorder, and Mood Disorders (NIH Bookshelf; PMC). Notably, conventional MRI and CT scans often fail to reveal clear abnormalities in people suffering from PCS, despite the presence of these functional deficits (NIH Bookshelf; PubMed). This cluster of residual symptoms is referred to as ‘Post-Concussion Syndrome’.

Symptoms of Post-Concussion Syndrome

- Attention deficits and difficulty sustaining mental effort are commonly seen in individuals with post-concussion syndrome (Mayo Clinic).

- Fatigue and tiredness frequently affect people after a concussion (NCBI Bookshelf).

- Impulsivity can emerge following a traumatic brain injury, sometimes leading to risky or inappropriate actions (ScienceDirect).

- Irritability and a low frustration threshold are often reported, sometimes resulting in outbursts or difficulty managing emotions (Headway).

- Temper outbursts have been observed as a behavioural effect of brain injury (Headway).

- Changes in mood, including depression and anxiety, are also common after a concussion (Cognitive FX).

- Learning and memory problems, such as trouble with concentration and memory, are typical symptoms (Mayo Clinic).

- Impaired planning and problem-solving abilities can arise after a concussion (ScienceDirect).

- Inflexibility and ‘concrete’ (rather than ‘fluid’) thinking may be present, making it harder to adapt to new situations (Headway).

- A lack of initiative is sometimes observed, with individuals appearing less motivated or proactive (ScienceDirect).

- Dissociation between thoughts and actions has been noted, where individuals may struggle to act on their intentions (NCBI Bookshelf).

- Communication difficulties, such as trouble expressing oneself or following conversations, are not uncommon (MSKTC).

- Socially inappropriate behaviours, including excessive disinhibition or not following social norms, are well-documented after brain injury (Cognitive FX).

- Self-centredness and a lack of insight, where individuals may not recognise their own issues or how their behaviour affects others, are frequently described (Headway).

- Poor self-awareness is a clinical concern, affecting outcomes and rehabilitation (PMC).

- Impaired balance, dizziness, and headaches are physical symptoms commonly reported in post-concussion syndrome (Physio-Pedia).

- Personality changes, such as shifts in emotional responses or overall demeanour, may persist after a concussion (Health.mil).

Although many people experience persistent symptoms after a brain injury, conventional scans like CTs or MRIs often fail to reveal any abnormalities. This diagnostic gap can lead to unfair stereotypes—individuals are sometimes labelled as “hot headed” or accused of having a “short fuse,” when these behaviours may actually stem from subtle, undetected brain changes (Neuropsychological Assessment, Lezak et al., 2012). These misunderstandings can result in misdiagnoses, such as mood or personality disorders, rather than recognising the neurological basis for the symptoms (Silver et al., 2009). Research shows that standard neuroimaging is often too crude to detect the microstructural or functional changes that underlie these issues (Bigler, 2013). More recently, advances in imaging have begun to reveal abnormalities in cases where traditional scans appear normal, underscoring the need for more sensitive diagnostic tools to accurately identify and address these injuries (Hillary et al., 2021).

Symptoms have an Organic Basis

There’s been a lot of debate around Post-Concussion Syndrome (PCS), especially since patients often report persistent symptoms even when standard scans show little or no injury. The question of whether PCS is psychological or rooted in actual brain changes has been the subject of ongoing research. Over the past three decades, mounting evidence from neuroimaging studies has shown clear organic, brain-based changes in people with PCS. For example, research using cerebral blood flow (CBF) imaging has found abnormal perfusion patterns in both children and adults with persistent post-concussion symptoms, linking these changes to symptom severity and recovery outcomes (Journal of Neurotrauma, JAMA Neurology, Journal of Neurotrauma 2021).

Neuropsychological testing consistently finds cognitive deficits in attention, memory, and executive function that correlate with PCS, even in the absence of visible structural damage on MRI scans (Neurology India, Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society).

Further, studies using evoked potential recordings and EEG have detected neurophysiological abnormalities in individuals with persistent post-concussion symptoms (Neuroscience), and both PET and SPECT imaging, as well as quantitative EEG (QEEG), have identified functional brain changes in PCS patients that are consistent with their reported symptoms (Clinical EEG and Neuroscience, Frontiers in Neurology). Many of the leading theories about PCS are now strongly supported by findings from QEEG and other advanced imaging methods, reinforcing that PCS has a demonstrable, organic basis.

Recent scientific literature shows that Post-Concussion Syndrome can be identified with a high degree of specificity using quantitative QEEG neuroimaging, which has demonstrated a sensitivity of 96% in detecting this condition (ResearchGate). When patients are fully informed about the benefits and limitations of these approaches, they may consider neurofeedback as part of a comprehensive treatment plan for Post-Concussion Syndrome. For more details, see the peer-reviewed paper by Dr. Jacques Duff on the use of QEEG and neurotherapy for this condition (ResearchGate).

Treatment of Post Concussion Syndrome

A multimodal approach is increasingly recognized as best practice in the treatment of post-concussion syndrome (PCS). Recommended components include patient education, active rehabilitation, nutrition, neurofeedback, and symptom-specific therapies, each contributing a unique facet to recovery (Brain Injury; JAMA Network Open).

Education and Reassurance:

Providing evidence-based information about PCS and its typical course can help reassure that symptoms have a cause, reduce anxiety, and empower patients. This remains a cornerstone of PCS management.

Active Rehabilitation:

Contemporary guidelines recommend a gradual, symptom-guided return to activity, often involving supervised aerobic exercise, vestibular therapy, and cognitive-behavioral strategies. Prolonged rest is discouraged, as it can contribute to physical deconditioning and mood disturbances (Sports Health).

Neurofeedback:

Neurofeedback is emerging as a promising, non-invasive intervention for individuals with persistent PCS symptoms, especially when cognitive, emotional, or sensory complaints are prominent. The technique involves monitoring the patient’s real-time brainwave activity (typically via EEG) and providing feedback, with the aim of training the brain toward more optimal function.

Research into neurofeedback for PCS is still developing, but several small clinical trials and case studies have reported positive outcomes. For example, improvements have been noted in attention, working memory, headache frequency, sleep quality, and mood regulation in patients who did not respond fully to standard interventions. The proposed mechanism is that neurofeedback assists in restoring disrupted neural networks and reducing maladaptive brainwave patterns that linger after concussion.

Protocols often target specific EEG markers associated with PCS, such as excessive theta or reduced alpha activity. Sessions are typically conducted over several weeks, and treatment is individualised based on the patient’s symptom profile and neurophysiological findings.

While the evidence base is not yet as robust as for other therapies, neurofeedback’s safety profile and early clinical results make it a reasonable consideration for select PCS patients who may not be responding to other therapies, especially when integrated into a broader, multidisciplinary program. Ongoing randomised controlled trials are expected to clarify its efficacy and optimal protocols.

Nutrition:

Nutritional counselling and targeted supplementation, indicated from blood tests, are being explored as adjuncts to PCS care. These interventions may support neuroplasticity, reduce neuroinflammation, and address deficiencies that could impede recovery. While the research is still evolving, some clinicians refer to dieticians or nutritionists to incorporate dietary assessments and nutritional recommendations into their multimodal plans.

Nonpharmacological and Pharmacological Therapies:

Nonpharmacological treatments—such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, vestibular rehabilitation, and supervised exercise—remain foundational for persistent PCS (JAMA Network Open). Medications may be used for symptom clusters like headache or insomnia, but are typically reserved for cases where nonpharmacologic options are insufficient (Springer).

Summary:

A contemporary, evidence-informed treatment plan for PCS is multifaceted. It weaves together education, active rehabilitation, nutritional support, and evolving therapies like neurofeedback, all tailored to the individual patient. As the research base for neurofeedback grows, it may become a more central pillar in the management of chronic concussion symptoms, offering new hope to those with lingering post-concussive difficulties.

Updated on: 10/02/2026 by: Dr. Jacques Duff – BA Psych; Grad Dip Psych; PhD; MAPS; MECNS; MAAAPB; MISNR; FANSA

Reviewed on: 21/02/2026 by: Bernard Ferriere - BA; Grad Dip App Psych; Dip Clinical Hypnosis; FCCP; MAPS; MASH; Clinical Psychologist