Causes & Symptoms of Post-Concussion Syndrome

Post-Concussion Syndrome symptoms can include attention deficits, concentration difficulties, learning difficulties, impulsivity, mood, and anger problems, as well as headaches and fatigue that persist for years after the advent of a minor closed head injury. Often, sufferers are treatment non-responsive. Frequently, patients are also diagnosed with co-morbid ADHD, Adjustment Disorder, Depression, and other psychiatric illnesses that have persistent symptoms.

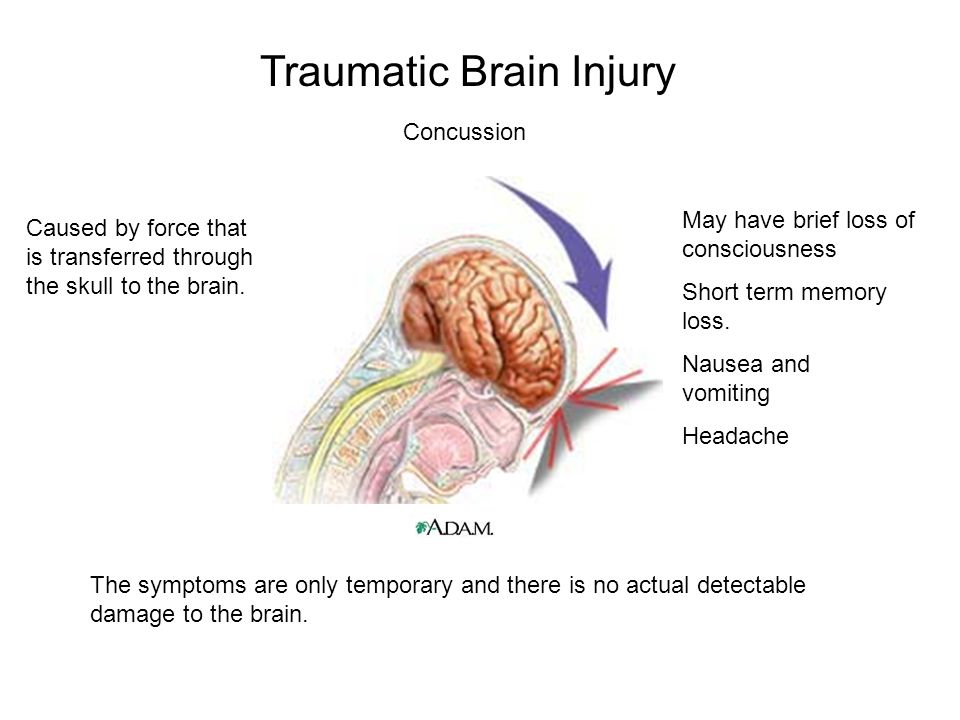

After the head receives a sharp blow, the force produces differences in the movement between the brain and the skull that can result in traumatic brain injuries (TBI). Although most injury is at the site of impact, the frontal and temporal regions become vulnerable to contusions due to percussion and the impact of shearing forces on delicate brain tissue [1]. A percussion wave which travels through brain matter can cause a ‘contre-coup’ (further contusion diagonally across the skill), and shear forces at the boundary between white and grey matter can result in axonal shearing [1].

The terms Post-Concussion Syndrome, or Post-Concussional Disorder, are used to describe a range of long-term residual symptoms. Although minor head injuries are generally considered benign, a significant number of people report persistent symptoms for weeks, months [2], or years after the injury itself [3-17]. There is a lack of evidence for these brain abnormalities on MRI and CT scans. The core functional deficits associated with Post-Concussion Syndrome overlap with those of Attention Deficit Disorder, Adjustment Disorder and Mood Disorders. In addition, sufferers often report memory and socialisation problems, frequent headaches, and personality change.

This cluster of symptoms is referred to as ‘Post-Concussion Syndrome’.

Symptoms of Post-Concussion Syndrome

The following are amongst the most reported symptoms of Post-Concussion Syndrome:

- Attention deficits, difficulty sustaining mental effort.

- Fatigue and tiredness.

- Impulsivity.

- Irritability and a low frustration threshold.

- Temper outbursts.

- Changes in mood.

- Learning and memory problems.

- Impaired planning and problem-solving.

- Inflexibility and ‘concrete’ (rather than ‘fluid’) thinking.

- Lack of initiative.

- Dissociation between thoughts and actions.

- Communication difficulties.

- Socially inappropriate behaviours.

- Self-centeredness and lack of insight.

- Poor self-awareness.

- Impaired balance, dizziness, and headaches [6, 15, 18, 19].

- Personality changes [20, 21].

Despite the existence of several chronic symptoms, the associated brain abnormalities cannot be detected in conventional structural neuroimaging tests, such as CT scans and MRI. Thus, the sufferer is often unfairly labelled as ‘hot headed’, having a ‘short fuse’, anger problems or, in some cases, misdiagnosed with a mood, personality, or psychological disorder.

Symptoms with an Organic Basis

The fact that the sufferer’s complaints seem to contradict ‘negative’ medical findings has been a source of controversy. The debate surrounds whether Post-Concussion Syndrome has an organic or psychological basis [4]. However, over the past 30 years, evidence points to an organic (brain based) aetiology (original cause) for Post-Concussion Syndrome. Evidence includes studies of cerebral blood flow, neuropsychological deficits and evoked potential recordings, as well as PET, SPECT, MRI, EEG and QEEG measures [22-30]. Most of the theoretical concepts that have been discussed and formulated are clearly supported by QEEG findings [31, 32].

The scientific literature indicates that Post-Concussion Syndrome can be identified with a high degree of specificity using QEEG neuroimaging and treated most effectively using Neurotherapy.

Here is a peer reviewed paper on the use of QEEG and Neurotherapy for Post Concussion Syndrome by Dr Jacques Duff.

References

- Thatcher, R.W., EEG operant conditioning (biofeedback) and traumatic brain injury. Clin Electroencephalography, 2000. 31(1): p. 38-44.

- Hugenholtz, H., et al., How long does it take to recover from a mild concussion? Neurosurgery, 1988. 22(5): p. 853-8.

- Slagle, D.A., Psychiatric disorders following closed head injury: an overview of biopsychosocial factors in their etiology and management. Int J Psychiatry Med, 1990. 20(1): p. 1-35.

- Fenton, G.W., The postconcussional syndrome reappraised. Clin Electroencephalogr, 1996. 27(4): p. 174-82.

- Ponsford, J. and G. Kinsella, Attentional deficits following closed-head injury. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol, 1992. 14(5): p. 822-38.

- Ponsford, J., S. Sloan, and P. Snow, Traumatic Brain Injury: Rehabilitation for everyday adaptive living. 1995, Hillsdale (USA): Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Zwil, A.S., M.E. Sandel, and E. Kim, Organic and psychological sequelae of traumatic brain injury: the postconcussional syndrome in clinical practice. New Dir Ment Health Serv, 1993(57): p. 109-15.

- Stevens, M.M., Post-concussion syndrome. J Neurosurg Nurs, 1982. 14(5): p. 239-44.

- Elkind, A.H., Headache and facial pain associated with head injury. Otolaryngol Clin North Am, 1989. 22(6): p. 1251-71.

- Fann, J.R., et al., Psychiatric disorders and functional disability in outpatients with traumatic brain injuries. Am J Psychiatry, 1995. 152(10): p. 1493-9.

- Munoz-Cespedes, J.M., et al., [The nature, diagnosis and treatment of Post-Concussion Syndrome]. Rev Neurol, 1998. 27(159): p. 844-53.

- Pelczar, M. and B. Politynska, [Pathogenesis and psychosocial consequences of Post-Concussion Syndrome]. Neurol Neurochir Pol, 1997. 31(5): p. 989-98.

- Harrington, D.E., et al., Current perceptions of rehabilitation professionals towards mild traumatic brain injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil, 1993. 74(6): p. 579-86.

- Binder, L.M., Persisting symptoms after mild head injury: a review of the postconcussive syndrome. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol, 1986. 8(4): p. 323-46.

- Hilton, G., Behavioral and cognitive sequelae of head trauma. Orthop Nurs, 1994. 13(4): p. 25-32.

- Hillier, S.L., M.H. Sharpe, and J. Metzer, Outcomes 5 years post-traumatic brain injury (with further reference to neurophysical impairment and disability). Brain Inj, 1997. 11(9): p. 661-75.

- Millis, S.R., et al., Long-term neuropsychological outcome after traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil, 2001. 16(4): p. 343-55.

- Hillier, S.L. and J. Metzer, Awareness and perceptions of outcomes after traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj, 1997. 11(7): p. 525-36.

- Johansson, E., M. Ronnkvist, and A.R. Fugl-Meyer, Traumatic brain injury in northern Sweden. Incidence and prevalence of long-standing impairments and disabilities. Scand J Rehabil Med, 1991. 23(4): p. 179-85.

- Malia, K., G. Powell, and S. Torode, Personality and psychosocial function after brain injury. Brain Inj, 1995. 9(7): p. 697-712.

- Max, J.E., B.A. Robertson, and A.E. Lansing, The phenomenology of personality change due to traumatic brain injury in children and adolescents. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci, 2001. 13(2): p. 161-70.

- Gerring, J., et al., Neuroimaging variables related to development of Secondary Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder after closed head injury in children and adolescents. Brain Inj, 2000. 14(3): p. 205-18.

- Voller, B., et al., Neuropsychological, MRI and EEG findings after very mild traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj, 1999. 13(10): p. 821-7.

- Jansen, H.M., et al., Cobalt-55 positron emission tomography in traumatic brain injury: a pilot study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry, 1996. 60(2): p. 221-4.

- Rudolf, J., et al., Cerebral glucose metabolism in acute and persistent vegetative state. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol, 1999. 11(1): p. 17-24.

- Bergsneider, M., et al., Cerebral hyperglycolysis following severe traumatic brain injury in humans: a positron emission tomography study. J Neurosurg, 1997. 86(2): p. 241-51.

- Matz, P.G. and L. Pitts, Monitoring in traumatic brain injury. Clin Neurosurg, 1997. 44: p. 267-94.

- Thatcher, R.W., et al., Biophysical Linkage between MRI and EEG Amplitude in Closed Head Injury. Neuroimage, 1998. 7(4): p. 352-367.

- Thatcher, R.W., et al., Biophysical linkage between MRI and EEG coherence in closed head injury. Neuroimage, 1998. 8(4): p. 307-26.

- Thatcher, R.W., et al., Quantitative MRI of the gray-white matter distribution in traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma, 1997. 14(1): p. 1-14.

- Shaw, N.A., The neurophysiology of concussion. Prog Neurobiol, 2002. 67(4): p. 281-344.

- Montgomery, E.A., et al., The psychobiology of minor head injury. Psychol Med, 1991. 21(2): p. 375-84.

- Duff, J., The usefulness of Quantitative EEG (QEEG) and Neurotherapy in the Assessment, and Treatment of Post-Concussion Syndrome. Clinical EEG and Neuroscience, 2004. 35(4): p. 1-12.

- Hughes, J.R. and E.R. John, Conventional and quantitative electroencephalography in psychiatry. Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 1999. 11(2): p. 190-208.

- Thatcher, R.W., et al., EEG discriminant analyses of mild head trauma. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol, 1989. 73(2): p. 94-106.

- Thatcher, R.W., et al., QEEG and traumatic brain injury: rebuttal of the American Academy of Neurology 1997 report by the EEG and Clinical Neuroscience Society. Clin Electroencephalogr, 1999. 30(3): p. 94-8.

- Gordon, E., Integrative neuroscience in psychiatry: the role of a standardized database. Australasian Psychiatry, 2003. 11(2): p. 156-163.

- Lubar, J.F., Discourse on the development of EEG diagnostics and biofeedback for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorders. Biofeedback and Self Regulation, 1991. 16(3): p. 201-225.

- Sterman, M.B., Sensorimotor EEG operant conditioning: Experimental and clinical effects. Pavlovian Journal of Biological Science, 1977. 12(2): p. 63-92.

- Sterman, M.B., EEG biofeedback: physiological behavior modification. Neurosci Biobehav Rev, 1981. 5(3): p. 405-12.

- Thompson, L. and M. Thompson, Neurofeedback combined with training in metacognitive strategies: Effectiveness in students with ADD. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 1998. 23(4): p. 243-263.

- Thatcher, R.W., Normative EEG databases and EEG biofeedback. Journal of Neurotherapy, 1998. 2(4): p. 8-39.

- Thatcher, R.W., EEG database guided neurotherapy, in Introduction to Quantitative EEG and Neurofeedback, A. Abarbanel, Editor. 1999, Academic Press: San Diego.

- Sterman, M.B., Physiological origins and functional correlates of EEG rhythmic activities: Implications for self-regulation. Biofeedback and Self-Regulation, 1996. 21(1): p. 3-33.